TLDR;

This video discusses the social context of the 19th-century Philippines, focusing on the influence of religious missionaries, the social classes during Spanish colonization, and the impact of policies and education on the native Filipinos. It also touches on the political landscape, including the implementation of the Cadiz Constitution, the rise of liberalism, and the Bourbon reforms.

- Religious missionaries played a crucial role in evangelizing and reducing the native population into organized towns.

- The social hierarchy was heavily influenced by the concept of "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood), leading to racial discrimination.

- Education was limited by class, with a curriculum heavily centered on religion and loyalty to Spain.

- The Cadiz Constitution introduced liberal ideas but was short-lived due to the return of absolutism under King Fernando VII.

- The Bourbon reforms aimed to improve the lives of the people but were often not implemented by Spanish officials in the Philippines.

Role of Religious Missionaries [0:35]

The establishment of Spanish colonization in the Philippines was significantly aided by religious missionaries. The Augustinians were the first to arrive in 1565, followed by the Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, and Augustinian Recollects. These missionaries were responsible for converting a large portion of the population to Christianity, with a majority subscribing to the Roman Catholic faith. They also implemented a policy called "reduccion," which involved relocating natives from remote areas to constructed towns known as pueblos. In these pueblos, the missionaries built homes, churches, marketplaces, and schools, often with the help of forced labor from the natives. They taught agriculture and created dictionaries to translate Filipino languages into Spanish, although they generally did not teach the natives to speak Spanish, except for a privileged few.

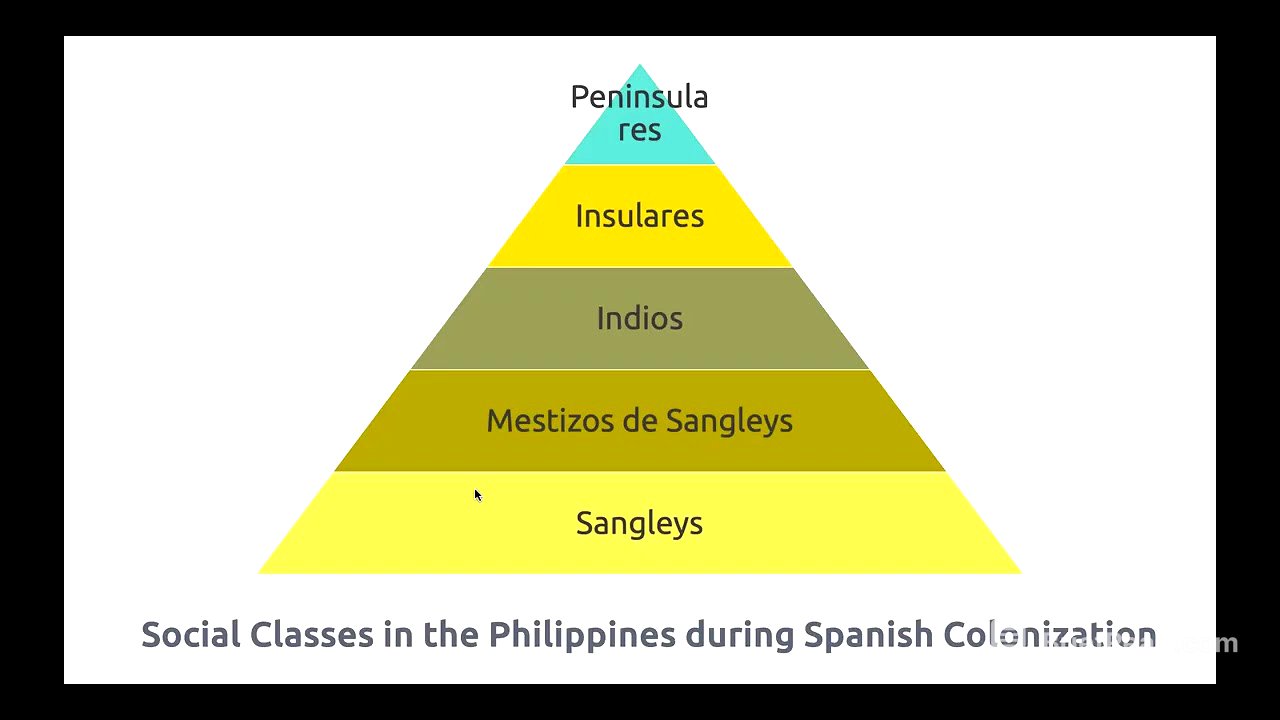

Social Classes During Spanish Colonization [4:17]

Philippine society during Spanish colonization was highly stratified. At the top were the peninsulares, full-blooded Spaniards from mainland Spain, who held the highest positions in government and the church. Next were the insulares, Spaniards born in the Philippines. Both peninsulares and insulares were exempt from paying taxes and providing forced labor. Below them were the Indios, the native Filipinos, who were subjected to forced labor and paid reduced taxes. The mestizos de sangle, of mixed native and Chinese descent, paid double the tribute. At the bottom were the Chinese, or sangle, who paid the highest tax rate but were not obligated to perform forced labor. Marginal groups included the Muslims (Moros) in Mindanao and the Simarones, who were either "untouched people" living in rugged mountains (remontados) or near shores.

Limpiesa de Sangre and Racial Discrimination [10:40]

The stratification was largely due to the concept of "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood), which caused significant racial discrimination. Peninsulares discriminated against insulares, viewing those born in the Philippines as not truly Spanish. This discrimination led to a late surge of Filipino clergy, particularly secular priests, who faced prejudice due to their upbringing. The phenomenon of not feeling like they belonged in society was widespread among Filipinos due to oppression and abuse. Peninsulares used their perceived superiority to maintain their position at the top of the social hierarchy, often exempting themselves from rules and obligations imposed on others.

Policies Affecting the Social Context [14:51]

Several policies affected the social context of native Filipinos. "Reduccion" concentrated natives into pueblos for easier control, religious instruction, and tax collection. "Polo y servicio" required males aged 16 to 60 to render service for one month, though exemption could be obtained by paying "falla." "Tribute" was an annual tax paid in cash or labor, with natives obligated to pay a colony tax. "Frailocracy" was a political system where friars had significant control over the political, social, cultural, and religious life of Filipinos, often using their moral authority to make life difficult for the natives.

Education During Spanish Colonization [17:55]

Access to education was limited by class, with peninsulares, insulares, and wealthy mestizos able to afford formal education provided by religious institutions. Native Filipinos had little to no access to higher education unless privileged or sponsored. Schools were primarily located in urban centers like Manila, and the curriculum was heavily religious, focusing on catechism, Christian doctrine, the Spanish language, and loyalty to Spain. Subjects included Latin, history, geography, mathematics, and philosophy, with an emphasis on rote learning. Women could receive technical education in skills like housekeeping, cooking, sewing, and embroidery, or enter "beatas" to train for motherhood. The education framework aimed to create docile subjects who were compliant and did not question authority.

Schools Established During the Spanish Period [23:59]

Several schools were established and operated by religious missionaries, including the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Colegio de San Juan de Letran, Ateneo de Municipal (now Ateneo de Manila University), and San Jose Seminary. Santa Isabel College was for women seeking vocational skills and motherhood training. The clergy had the power to expel or censor students deemed radical. However, schools like Ateneo, Letran, and UST produced "illustrados," enlightened individuals who sought to improve their country, such as José Rizal.

Political Context: Cadiz Constitution and Liberalism [27:04]

The Cadiz Constitution, a liberal constitution declared in 1812, was briefly implemented in the Philippines. Don Ventura de Los Reyes, a Freeman merchant, approved its implementation, which vested equity and individual freedom in residents. However, it was short-lived, as King Fernando VII of Spain, a despotic leader, abolished it in 1814, leading to severe absolutism in the Philippines. This political climate influenced national heroes like Rizal, del Pilar, and Lopez Jaena, who embraced liberalism, emphasizing individual liberty, rights, and equality of opportunity.

Bourbon Reforms and Complacency [33:40]

To counter the rise of liberalism, the Bourbon monarchy in Spain implemented reform policies to ease the lives of the people, including reassessing the education system in the Philippines in 1863 and providing vaccines. However, Spanish officials in the Philippines often agreed with the reforms but did not implement them, a practice known as "complacency." They believed that implementing these reforms would alleviate the burdens on the colonized people. The video concludes by asserting that there is no such thing as a benevolent colonizer or tyrant, emphasizing the exploitative nature of colonization.