TLDR;

This video explores the evolution of drug smuggling submarines used by Colombian cartels since the 1970s. It covers their initial success, the construction of submarines in the Amazon jungle, attempts to acquire nuclear submarines, and the shift towards more advanced, stealthier fiberglass and electric submarines. The video also details a specific case of a submarine traveling to Spain and the ongoing efforts to combat this method of drug transportation.

- The rise of Colombian drug cartels in the 1970s and their innovative use of submarines for smuggling.

- The challenges and adaptations in submarine construction and technology.

- The economic impact and risks associated with drug submarine operations.

The Rise of Cocaine and Cartels [0:02]

In the 1970s, cocaine became a global drug, prompting Colombian criminals to enter the business due to Colombia's abundant cocaine supply. They aimed to profit by transporting cheap cocaine from Colombia to the United States, where it could be sold at high prices. This venture proved highly successful, leading to the rise of smugglers and the formation of powerful cartels that eventually became more influential than the Colombian government itself. By the 1980s, these cartels were determined to transport drugs to America by any means necessary, including land, sea, air, and even helicopters and planes, which they could easily afford due to their immense wealth.

The Submarine Solution [2:07]

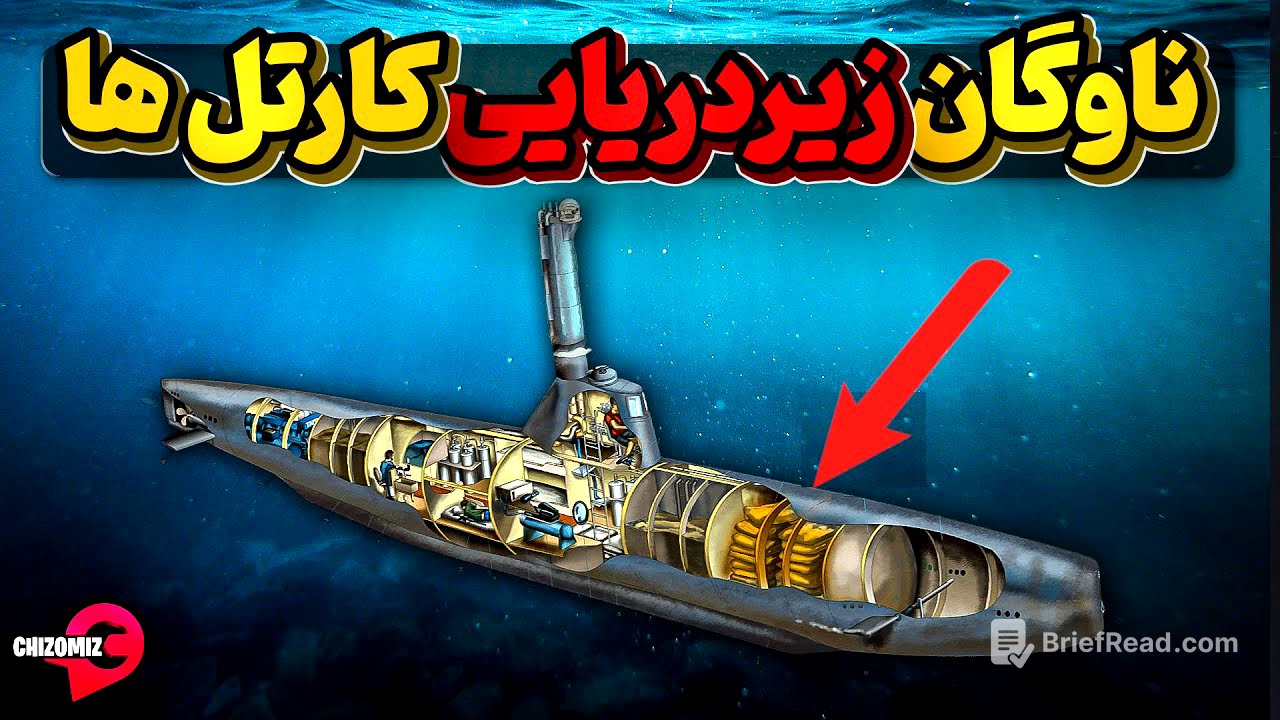

As land routes became more restricted and air and sea controls intensified, cartels sought new methods of transportation, leading them to explore underwater routes. Pablo Escobar's cartel, along with others, began constructing submarines to deliver goods underwater, even considering direct deliveries to Europe. Despite the challenges of building submarines, they hired engineers and acquired equipment, establishing secret construction sites in the heart of the Colombian jungle within the Amazon rainforest. In 1988, the US Coast Guard intercepted the first submarine near Boca Raton, Florida, discovering it was used for drug smuggling, highlighting the need to monitor underwater activity.

Nuclear Ambitions and Jungle Builds [4:20]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Colombian cartels attempted to purchase a nuclear submarine from the newly independent republics. They sought contacts, such as Leonid Feinberg in Ukraine, to facilitate the deal, offering $35 million. However, acquiring a nuclear submarine proved impossible due to monitoring by NATO and the US. Consequently, the cartels focused on building their own submarines in the jungle. In the years following 2001, over 200 of these submarines were seized by the US and Mexican Coast Guards, highlighting the scale of underwater drug trafficking.

Economics and the Submarine King [6:39]

Submarines became a profitable method for transporting drugs to the US and Europe, capable of carrying tons of material, significantly increasing cartel profits from hundreds of thousands to hundreds of millions of dollars. For example, a submarine carrying 7 tons of cocaine to Florida could be worth $200 to $300 million. In 2022, Oscar Moreno Ricardo, known as the "Submarine King," was arrested by Colombian police for his involvement in building these submarines in the Amazon jungle, where they established production workshops along the rivers.

Navigating the Waters [7:52]

The cartels utilized rivers in the Amazon forests to access both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, using cheap, semi-submersible boats with limited technology, mainly consisting of a diesel engine, fuel tank, and cocaine. These boats, with only their heads above water, were more susceptible to being caught. To avoid detection and destruction of evidence, the submarines were equipped with valves to sink them, with the crew abandoning ship upon arrival or when intercepted.

The Journey to Spain [9:57]

In 2022, a Colombian cartel submarine, piloted by a former Spanish boxer named Alejandro Augusto Álvarez, journeyed to Spain via the Atlantic Ocean. The submarine, lacking GPS or computer components to avoid radar detection, relied on a simple mechanical compass for navigation over 600 kilometers. Unlike the shorter trips to America, this submarine needed to be larger to accommodate more fuel for the two-week journey. The submarine carried 3 tons of cocaine, less than the amounts typically transported to America due to the need for more fuel and the higher price of cocaine in Europe.

Trials and Tribulations at Sea [12:08]

The submarine lacked basic amenities like toilets, with the crew using plastic bags for waste. Alvarez encountered adverse water currents, causing them to consume more fuel than anticipated. After 27 days, running low on fuel, they surfaced, where they were spotted by the Spanish Coast Guard. The crew opened the hatch to sink the submarine and were arrested. The Spanish Coast Guard recovered the submarine, finding 3,068 kilos of cocaine worth over 150 million euros. Álvarez and his Ecuadorian crew were sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Technological Advancements and the Future [14:37]

The capture of the submarine near Europe shocked European authorities, prompting increased vigilance. To counter losses from captured submarines, cartels began producing advanced, 25-meter-long submarines with modern periscopes and fiberglass construction for stealth. These lighter submarines could carry more cargo and consume less fuel. The fiberglass submarines, never captured, were developed using technology gleaned from submarine corpses found near the shores. The cartels also developed electric submarines, towed by ships to avoid detection, which have also never been caught. Despite the success of these submarines, which reach their destination over 80% of the time, there is the possibility of future innovations that could lead to their capture.