TLDR;

This video discusses the reign of Elizabeth I of England, covering the political and religious landscape she navigated, including challenges from Catholic factions and foreign powers like Spain and France. It also explores the social and economic transformations during her rule, such as the rise of the gentry and merchants, the expansion of English maritime power, and the cultural flourishing marked by figures like Shakespeare. The defeat of the Spanish Armada and the evolving social structure are highlighted as key factors in England's growing power.

- Elizabeth I navigated religious and political challenges, balancing Protestant and Catholic interests.

- England's victory over the Spanish Armada marked a turning point in its rise to power.

- Social and economic changes, including the rise of the gentry and maritime trade, contributed to England's strength.

Introduction: Elizabeth's England [0:01]

The video introduces the historical context of Elizabeth I's reign, starting with the Tudor dynasty. Following the death of Henry VIII in 1547, his three children each took the throne, but none produced an heir. Edward VI, the first to rule, shifted the Church of England closer to Protestantism. Henry VIII had initiated a schism, separating the English Church from papal authority without fully embracing Lutheran ideas.

Succession Crisis and Religious Tensions [0:07]

After Edward's death, his sister Mary, a devout Catholic, ascended to the throne with the goal of restoring Catholicism in England. She married Philip II of Spain, who aimed to prevent an alliance between England and France against him. Mary's reign was marked by the persecution of Protestants, leading to her being known as "Bloody Mary." Her actions also threatened those who had acquired church lands during her father's reign, creating further unrest.

Elizabeth I's Rise to Power and Political Strategy [1:39]

Following Mary's death in 1558, Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn, was quickly crowned. Catholics viewed Elizabeth as illegitimate due to their non-recognition of Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn, and they suspected her of Protestant sympathies. Both France and Spain sought to control England through marriage alliances with Elizabeth. Facing internal and external threats, including plots to replace her with Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth adopted a cautious political strategy, playing her enemies against each other. She even secured support from Philip II to prevent a Franco-English alliance.

Domestic Policies and Religious Settlement [3:03]

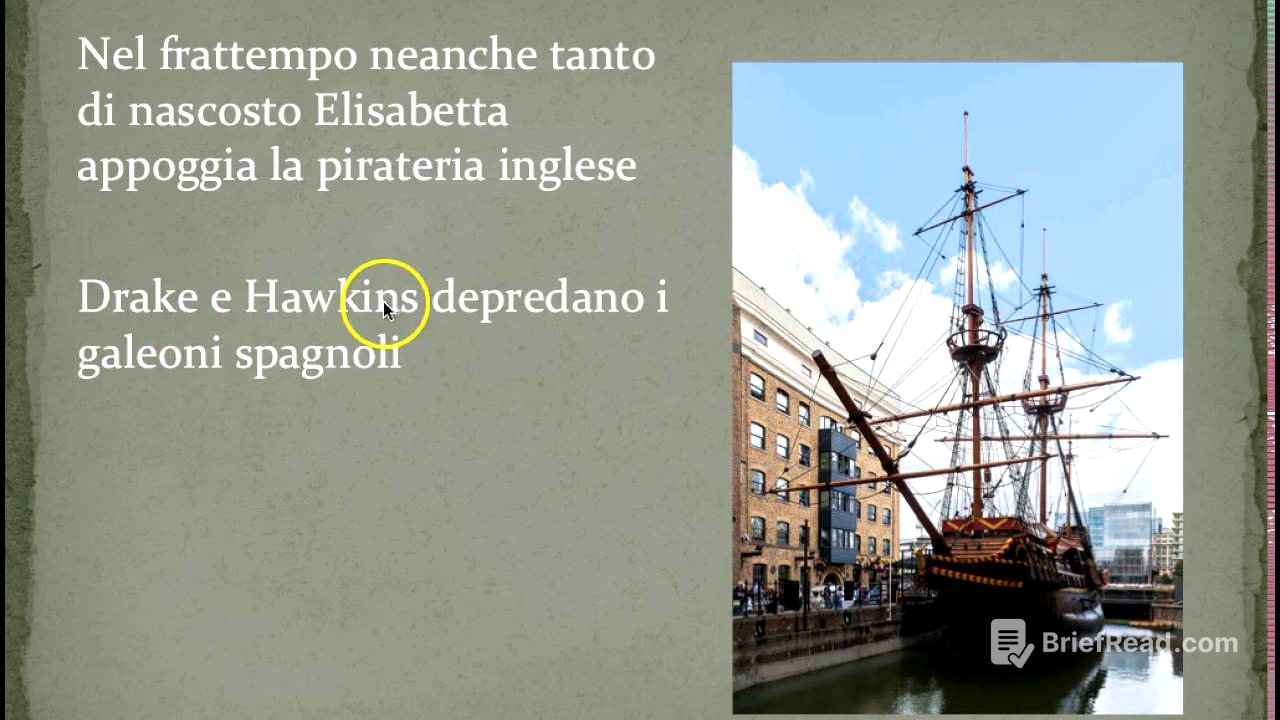

Within England, Elizabeth firmly defended her authority, harshly suppressing a Catholic conspiracy. She later captured and executed Mary Stuart. While not officially endorsing piracy, Elizabeth allowed English pirates to raid Spanish galleons laden with silver from the Americas. Figures like Drake and Hawkins led these expeditions, organised as joint-stock companies in which the Queen had a stake. In religious matters, Elizabeth aligned with the Protestant sentiments of Parliament, resisting Catholic interference in the Church of England. However, she faced challenges in Ireland, which remained largely Catholic and resented a Protestant queen.

Religious Reforms and Foreign Relations [4:18]

Elizabeth reinstated the Anglican Church through the Act of Supremacy and imposed the Book of Common Prayer via the Act of Uniformity, reflecting Protestant ideals, particularly those of Swiss reformer Zwingli. These acts were implemented with some tolerance towards Catholics and Calvinists (known as Puritans in England). Elizabeth supported Calvinists in Scotland, led by John Knox, and aided Calvinist rebels in the Netherlands. These actions led to increasing tensions with Spain, which unsuccessfully supported plots against Elizabeth.

The Spanish Armada and its Defeat [5:26]

Philip II, believing that suppressing the Dutch Revolt required defeating England, assembled the Spanish Armada. The execution of Mary Stuart served as the catalyst for conflict. In 1588, the Armada sailed towards the English Channel to transport troops from the Netherlands to England. The English fleet, though of similar size, avoided close-quarters combat and boarding, instead using long-range artillery to decimate the Spanish ships.

Aftermath of the Armada and Shifting Power Dynamics [6:30]

Although not completely destroyed, the Spanish Armada was significantly weakened by storms during its return journey. This led to a coalition between England, France, and Dutch rebels against Spain, resulting in a prolonged and costly war that continued after the deaths of both Philip and Elizabeth. Despite Spain's larger population and resources, England's victory was attributed to its evolving social structure.

Social and Economic Transformation in England [7:32]

English society underwent significant changes during the 16th century. The power of the traditional nobility declined, while the gentry (small provincial nobility) and London merchants grew wealthier and more influential. The gentry, often of bourgeois origin, adopted a modern approach to land management, viewing it as an investment. Alongside them, a rising class commercialised products from England's primary textile industry.

Maritime Expansion and Commercial Growth [8:37]

England increasingly looked to the sea for its future, with English ships dominating trade in the North Sea, Baltic, Mediterranean, and Atlantic. The Royal Exchange in London facilitated trade, with shares in privileged companies being among the most traded items. These companies, such as the Muscovy Company, the Levant Company, and the Guinea Company, held monopolies over trade with specific regions. The East India Company became particularly famous.

Exploration, Colonisation, and Cultural Renaissance [9:30]

Many merchants turned to piracy, and England began to covet Spanish colonies in America. English explorers ventured to the coasts of North America, drawn by the rich fishing grounds off Newfoundland. Sir Walter Raleigh founded a colony named Virginia in honour of Elizabeth. The era also saw a cultural renaissance, with public schools providing a common cultural foundation for the ruling class. Playwrights like Shakespeare and Marlowe created works that appealed to audiences of all classes, spreading humanist ideas and perspectives.